In a bid to mobilize the world’s governments and other stakeholders to take concerted action to close the loop on plastic waste, the United Nations is negotiating a Global Plastics Treaty with all of its members. Half way through the complex process adaPETation® looks at the pitfalls of getting the world to agree on closing the loop on plastic waste.

It’s easy to agree on something – plastic pollution is bad. How to prevent it from happening is the complicated part.

Efforts to bring about a global treaty to bring an end to plastic pollution are progressing within the halls of the United Nations following preliminary intergovernmental negotiating committee (INC) meetings in Uruguay (November) and Paris (June). Next stop Kenya in November before two more meetings in Canada and South Korea in 2024, before a final treaty is signed in 2025.

The stakes are high for everyone. Success for the latest United Nations multilateral agreement looks like the Montreal Protocol, widely accepted to have reversed the depletion of the Ozone layer and heralded as an example of what the world’s leaders can do when they work together.

Failure looks more like the Paris Agreement signed in 2015, which was designed to restrict greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming to 1.5% by the end of the century even though we are dangerously close to hurtling through that landmark less than a decade after it was signed. Multilateral frameworks like the Paris Agreement and the Global Plastics Treaty highlight the difficulties of reaching a global consensus on the most pressing issues we face as a species.

In the build up to the last meeting in Paris, the UN released an extensive report drafted by one of the adaPETation® podcast interviewees, Yoni Shiran, plastics lead for Systemiq, which draws heavily on the experience in Europe and its systems change approach to create a clear path to Net Zero for the plastics industry.

It lays out an almost irresistible argument for curtailing dramatically plastic pollution and offers a clear path to make it happen. It all seems so easy on paper.

The report, United Nations: Turning off the Tap: How the world can end plastic pollution and create a circular economy, proposes a systems change approach to address the causes of plastic pollution, “starting by reducing problematic and unnecessary plastic use, redesigning the system, products and their packaging and combining these with a market transformation towards circularity in plastics. This can be achieved by accelerating three key shifts – reorient and diversify, reuse, and recycle, – and actions to deal with the legacy of plastic pollution,” the report says.

The Key Objectives

The adoption of a systems change approach based on plans already being implemented in Europe, the UN says, provides a “compass” for governments and an ambitious action plan for businesses to end plastic pollution by 2040, highlighting how a series of circularity measures would offer a dramatically better vision compared to the continuing with business-as-usual. The measures proposed would:

- Slash plastic pollution by 80%.

- Halve single-use plastics production.

- Offer the global economy a net-saving and avoid externalities of USD$4.5trn by 2040.

- Create 700,000 jobs, mostly in low-income countries.

All of this can be done with technologies and solutions that already exist but, the report says, it “requires urgent simultaneous action across borders. A five-year delay in executing the necessary shifts mean higher costs and additional 80 million metric tons of plastic pollution by 2040.”

The savings are brought about by turning off the tap upstream and strengthening waste management systems downstream. Both are important.

Environmentally and Financially Sound

Implementing a systems change approach includes the widespread roll out of reuse, recycling systems and improved waste management. It not only makes environmental sense it makes financial sense. According to the report, overall savings of USD$1.3trn are up-for-grabs when considering investment, operations and management costs and recycling revenues. A further USD$3.3trn is saved from avoided externalities –environmental damages– making a total saving of more than $4.6trn between 2021 and 2040.

That’s a big number. The report’s authors make a compelling argument to influence governments to pursue these savings for their citizens when they write: “These results point to a considerable societal value emerging from increasing the sustainability of the plastics economy: for each dollar of conventional (direct) cost saved a further two dollars of societal damage (indirect cost) are also avoided.”

The key to disrupting the current throwaway culture of business-as-usual and single use plastics is to dampen demand for plastic as well as to increase recycling rates and the use of recycled material. An increase in recycling is required for all sorts of hard to recycle plastics and not just the most widely recycled material, PET. Likewise a shift towards higher adoption of reuse systems, an area where PET has a big role to play in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, is crucial for dampening the demand for plastic.

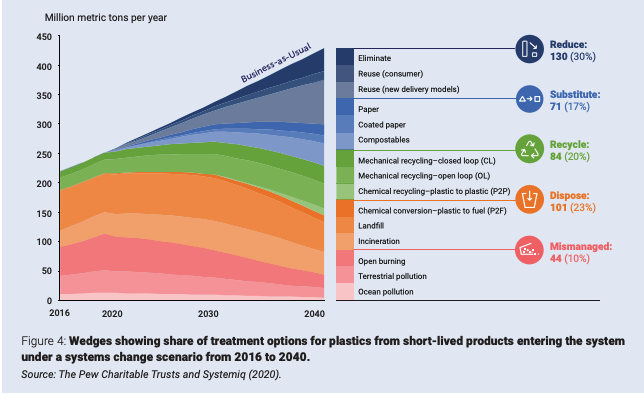

Increasing access to reuse systems globally is seen as the biggest lever to achieve the landmark 80% reduction in plastic waste. Extending reuse systems it is estimated will bring about a 30% reduction in single use plastics or a saving of 130m metric tons per year considerably reducing the need for new recycling capacity further downstream.

Substitution of plastic for other materials like paper and compostable materials would further reduce 71m metric tons a year, says the report while increased recycling would reduce waste by another 84m metric tons. Better waste management could account for 145m metric tons less plastic pollution a year, according to the report.

Joan Marc Simon, director of Zero Waste Europe says a concerted shift to reuse –prompted by the roll out of legislation and reuse mandates being introduced in Europe and by the adoption of these systems by leading consumer goods brands– is essential for the treaty to be a success.

“I think the increase in reuse systems is going to be a trend that is going to be unstoppable because it makes environmental sense and it makes economic sense,” he says. “The good news is that I think that consumer brands want to find a solution for this. They don’t want to see their brands later and be on the front page of newspapers.”

The inclusion of chemical recycling and the possibility of carbon capture solutions as part of the solution offer brands the prospect of increasing recycling and also notably reducing the carbon footprint of their packaging.

“In the material cycle I hope we can drive down the material use. You need a whole basket of solutions for this,” says Freya Burton, chief sustainability officer at LanzaTech. “It’s not just one technology approach. It’s not just mechanical recycling. You need everything. And that’s what’s still missing is that carbon recycling element beyond plastic recycling,” she says.

The treaty is championing technologies that already exist, but has yet to fully embrace more experimental ones like LanzaTech’s innovative solution that captures carbon from Chinese steel mills to convert it into one of the components used to make PET.

“There’s a strong push that seems practical, it’s not something that’s based on technologies that don’t exist. Some of them are at an early stage but they’re directionally scaling so I’m hopeful. I think the behavior of consumers and what they want will drive the brands to make changes,” says Burton.

“You know, you’re already seeing that now with refillable options and taking back bottles and reputationally brands really do see the problem. If you have a drink or food brand and your packaging gets washed up on a beach, that is a big reputational risk now more than ever with social media. So I think there’s reason to be hopeful because there’s a lot more push both from the consumer and brand commitments on what they want to do to meet their environmental targets.”

Moving from Theory to Realpolitik

The need to gain global consensus is highly likely to result in important tradeoffs that –early indications suggest– will limit the treaty’s final reach. The likelihood that any agreement will need to be unanimous, appears to have upended any attempt to shape a treaty in line with the higher goals of the Paris Agreement on greenhouse gas emissions.

“Where I see actually the challenges of this process is that it would make sense that the plastic treaty is connected to the global climate agreement so that actually the plastic treaty is consistent with keeping global warming under 1.5 warming,” says Simon.

“We should have a treaty that is actually consistent with the climate agenda, which actually poses the question of how we are going to manage with a lot less plastic because it’s impossible to get there with these levels of plastic production. We don’t have the resources to extract this and it’s completely incompatible with the climate agenda. And that begs a question: how much plastic is necessary? And all of that is for the moment, not being discussed,” says Simon.

“The global treaty on climate says overall we have 400 gigatons of CO2 equivalent to emit, of which plastic has a budget of around 15 gigatons. But if we continue business as usual, plastic will actually take a budget of 125 gigatons, which is more than all the other materials – more than steel, concrete, aluminum. So for me, my view is that we should have a treaty that is actually consistent with the climate agenda.”

Plastic’s role in a bigger picture is a theme that is echoed by others. Bob Lilienfeld, founder of the Sustainable Packaging Research, Information, and Networking Group (SPRING), asks why the treaty is focused only on plastic when waste from other materials is of equal concern.

Why isn’t the goal, he argues: “Something more along the lines of ‘optimize source reduction and circularity in order to reduce litter, landfilling, greenhouse gas generation, and virgin material use’? Further, a circular economy shouldn’t be a goal. It should be a strategy that helps lead to a goal, something along the lines of ‘minimize all types of waste in order to allow the Earth and its variety of ecosystems to remain healthy, vibrant, and sustainable’,” he argues.

Who’s Going to Pay to Break Free of Business-As-Usual?

Ultimately the ability to implement the ambitious changes required to bring about a paradigm shift and put an end to the linear business-as-usual approach will depend on overcoming some powerful vested interests.

The final reach and implementation of the treaty will very much depend on the weight brought to bear by the world’s largest plastic producers and this is likely to be the biggest hurdle to changes, according to Simon.

In particular, the need to level the playing field between virgin fossil fuels and circular solutions like reuse systems as well as the brands and packaging companies betting on higher quantities of recycled material will probably require widespread adoption of a proposed taxation on virgin plastic tax of $500 / metric tons.

A virgin plastic tax of the order of $500 / metric tons, the UN argues, could generate an additional cumulative revenue of USD$1.1trn between 2025 and 2040 which would be higher than the total capex required in the same period and almost 16% of the cost of externalities between 2021 and 2040.

“If such a levy were to be invested into an international circularity fund, to leverage private financing, it could thus finance the capital expenditure as well as part of the operations expenditure required for the systems change scenario and greatly accelerate the transition,” says the report.

“The key question here is what role is the oil industry going to play?” says Simon. “Because clearly they have an interest in selling more plastic and that’s what is in the end affecting the political will. Let’s not forget that many political parties are financed by the oil industry. So we’ll see.”

The Waste Management Treaty

Any resistance or curtailing of measures to dampen demand, is likely to ensure that the treaty has to work even harder on bolstering waste management and stimulating recycling to increase the amount of recycled material in all products from 2040.

To increase the amount of post-consumer recycled content in all new products from circa 6% in 2020 to 14% globally (i.e. 69 MMt) by 2040 it is estimated that the industry will need to expand waste collection rates in middle and low-income countries to 90% in urban areas and 50% in rural, supporting the informal collection sector.

In the next 5 years, this will require an increase in the global mechanical recycling capacity by 50% versus 2016, from ~43 MMt to ~65 MMt the equivalent to growing mechanical recycling rate of short-lived plastics from 14% in 2016 to 20% in 2028).

By 2040, the world will need to double annual mechanical recycling capacity globally from 43 MMt to 86 MMt (equivalent to growing mechanical recycling rate of short-lived plastics to 35% globally).

An enhanced ambition could triple mechanical recycling capacity to 129 MMt. which would cost an incremental capex of approximately USD$33 billion net present value (NPV) from 2021 to 2040 and opex of approximately USD$140 billion NPV from 2021 to 2040 for the recycling infrastructure.

Tripling rather than doubling global recycling capacity would save costs for virgin plastic production and plastic conversion as follows: capex USD$185 billion NPV from 2021 to 2040 and opex USD$290 billion NPV from 2021 to 2040.

In other words, tripling recycling capacity (from the capacity in 2016) instead of ‘only’ doubling it would create a net cost saving overall.

The critical condition for this to work is ensuring that this extra amount of plastic waste, that would otherwise go to landfill, can be designed to be safely mechanically recycled and that the economics of sorting and mechanical recycling are attractive enough to justify these investments.

“An ambitious legally binding instrument agreed by the end of 2024 could set the enabling conditions and economic incentives to make this possible, including transparency and controls on or criteria for plastics composition,” says the UN report.

While the possibility of reaching agreement on limits to greenhouse gas emissions and dampening demand seem to be beyond this treaty, the business opportunities associated with bulking up global waste management systems make this a more attractive outcome for many of the most powerful stakeholders.

“The minimum common denominator that all the countries in the negotiation so far agree on is that all the countries in the world should have the infrastructure to manage waste,” says Simon. “Because it’s the only thing we all agree on and because even though it’s not yet decided, it’s quite likely that we’re not going to have a majority voting, we’re going to have unanimity, the only thing that the countries are going to be able to agree upon altogether is actually to build infrastructure around the world,” he predicts.

“It’s also a good business opportunity to mobilize money and go into debt at the global level so that lots of companies get to build lots of recycling and collection infrastructure. So, because it’s a business of opportunity and because you have a political consensus, I think that’s the minimum we’re going to get,” he says.

If you like this content and would like to help close the loop on plastic waste then join the AdaPETation Network by clicking on the button below.

Share it