How the Ellen MacArthur Foundation & the New Plastics Economy changed the conversation taking place around plastic waste and packaging.

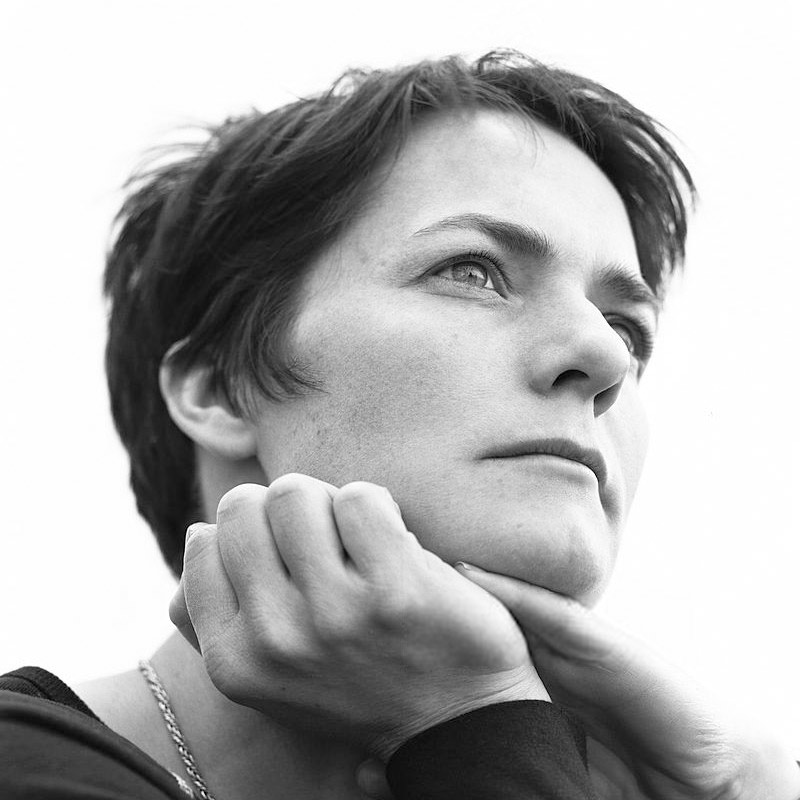

In 2005, the year that Ellen MacArthur broke the world record for sailing non-stop around the world single-handedly, there were 263 million tonnes of plastic being produced each year with less than 10% of that being recycled.

In the 71 days, 14 hours, 18 minutes 33 seconds, she took to navigate 27,354 nautical miles (50,660 km) the industry would have produced 51.8 million tonnes of plastics, of which 41.5 million tonnes would have piled up in landfills and as much as 1 million tonnes would have entered the oceans carrying MacArthur to her world record.

For someone used to living in a boat and packing the absolute minimum of resources in order to be as light and fast, as possible, the shock of arrival back on land to see how recklessly people were behaving with the world’s resources prompted an unexpected change in direction that would have a profound impact on the plastic and food packaging industries.

In 2009, MacArthur took the decision to quit competitive sailing, plotting a new course, a deep dive into waste in search of solutions. She found them in the systems thinking and biomimicry of thought leaders like Donella Meadows, Joseph Bragdon, Janine Benyus, Paul Hawken, Herman Daley, Walter Stahel, that inspired her to create the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF).

Her goal, to engage with industry leaders and steer them away from the current economic paradigm of “take, make, dispose” towards a more sustainable economic vision.

“I realized that on land we don’t see things as precious any more,” she said at the time of her decision to quit sailing and dive into activism.

“We take what we want. And it started to make me think. I was looking at plans for the future and it hit home to me. This world, that I thought as a child was the biggest, most adventurous place you could imagine, is not that big. And there’s an awful lot of us on it. And we’re not managing the resources that we have as you would on a boat because we don’t have the impression that these resources are limited.”

This wasteful way of doing business needed to be replaced by something more akin to the readily available examples happening around us all the time.

Putting Life at Center

MacArthur’s plan to bring things back into balance involved turning to Mother Nature for guidance. At the heart of everything would be the concept of putting nature at the center and replicating the cyclical way mother nature creates abundance from waste.

Simple evolutionary principles converted into revolutionary new ways of thinking.

“Living systems have proven themselves to create an abundance of stuff and successfully for billions of years,” says MacArthur. “It looks almost like now we’re trying to operate outside the rules like our operating system is broken, we’re trying to impose a linear system on a circular world.”

In nature, she says: “Waste equals food. Waste does not exist in living systems”.

Placing nature at the heart of all economic activity – replacing mankind’s ego with the spirit of eco – gave her foundation its purpose, to build a new circular economy that would mimic nature, to re-shape the world’s economic system.

In 2013, the mission was given a name, Project Mainstream, with the goal of making systems thinking the new paradigm.

A core of CEOs from nine companies – Averda, BT, Desso BV (a Tarkett company), Royal DSM, Ecolab, Indorama, Philips, SUEZ and Veolia – helped shape its direction and the need to prioritize led the group to take aim first at the plastics industry.

An “iconic” linear application, one of the worst proponents of the take, make, dispose consumption pattern of the 20th century, the plastics business was urgently in need of a rethink.

For all of its undisputed benefits in helping to reduce food waste and the transportation and environmental costs for the food industry of both, the material “has an inherent design failure: its intended useful life is typically less than one year; however, the material persists for centuries.”

It was also one of the most inefficient industries on the planet. An investigation undertaken in cooperation with the McKinsey & Company and the World Economic Forum determined that plastic packaging’s after-use externalities, plus the cost associated with greenhouse gas emissions from its production, was costing the planet $40 billion a year — far exceeding the plastic packaging industry’s annual profits.

The economics of the industry were every bit as wasteful as it was damaging to our environment. With EMF’s report estimating that the plastics industry was sending goods worth over USD$2.6 trillion annually to the world’s landfills and incineration plants.

Furthermore evidence showed that shifting to a circular model could generate a $706 billion economic opportunity, for the plastics industry, of which a significant proportion is attributable to packaging.

It’s estimated that after its first-use cycle, 95% of plastic packaging with a value of $80 billion – $120 billion annually, is lost to the economy a year and that a third of plastic packaging ends up polluting our natural systems such as the ocean or clogging up urban infrastructure.

All of these inefficiencies were deemed opportunities too big to ignore.

Rethinking the future of plastics

EMF launched the New Plastics Economy at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos in January 2016.

It was a wake-up call to the world with a call to action to move beyond the small-scale and incremental improvements currently being pursued to improve the industry’s negative impact on the environment and achieve a systemic shift towards a new circular model for the industry.

Existing improvement initiatives would need to be complemented and guided by a concerted, global, systemic and collaborative initiative to match the scale of the challenge and the opportunity.

What made the initiative ground-breaking and proved fundamental in its early success, was its willingness to work with the industry’s ‘worst offenders’ knowing that failing to do so would condemn the project to a position on the sidelines.

Rather than chastising plastic producers from an ivory tower, it chose instead to engage with the world’s most important companies in what it called a ‘race to the top’.

Collaboration would be required to overcome fragmentation, the lack of alignment between innovation in design and after-use, and lack of standards – all challenges that needed to be resolved for the initiative to have any chance of success.

Consumer goods companies, plastic packaging producers and plastics manufacturers would play a critical role, as they determine what products and materials are put on the market.

City planners controlling the after-use infrastructure in many places would be needed as hubs for innovation.

Recycling businesses involved in collection, sorting and reprocessing would be an equally critical part of the puzzle.

Policymakers would play an important role in enabling the transition by realigning incentives, facilitating secondary markets, defining standards and stimulating innovation.

NGOs would be needed to help ensure that broader social and environmental considerations are taken into account.

The foundation challenged companies identifying themselves as innovators to look at how they could design waste out of their systems and processes and brought the best talent in the world together to help.

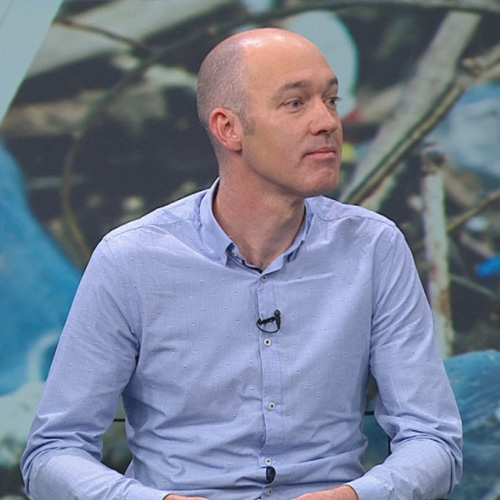

“The New Plastics Economy is an exciting opportunity to inspire a generation of designers to profoundly rethink plastic packaging and its role in a system that works,” says Tim Brown, the CEO of IDEO, the foundation’s principal design partner.

The Race To The Top

In the new plastics economy, it was argued, plastic should never become waste or pollution. To achieve this the focus was placed on three actions required to achieve a circular economy for the industry.

“Eliminate all problematic and unnecessary plastic items. Innovate to ensure that the plastics we do need are reusable, recyclable, or compostable. Circulate all the plastic items we use to keep them in the economy and out of the environment.”

It was no coincidence that some of the first companies to sign up to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation were those that already belong to a group of companies that already mimic nature in their decision making process.

Google’s chief executive Eric Schmidt backed the project through the Schmidt Family Foundation in 2013, and other early adopters that signed up in the same year included Coca-Cola, Marks & Spencer, IKEA Group, Morrisons, Tarkett, FLOOW2, Heights, iFixit, Ricoh, Vestas, WRAP, Turntoo, and Desso.

Polymer manufacturers; packaging producers; global brands; representatives of major cities focused on after-use collection; collection, sorting and reprocessing/recycling companies as well as industry experts and academics were all part of the team that worked to shape the project.

Companies like Unilever and Nike – of the Global LAMP index – 60 corporate pioneers in living asset stewardship – joined the mission in 2014, pledging themselves to the shift towards a circular economy ahead of the unveiling of the New Plastics Economy in 2016.

Since it’s launch more than 1,000 companies including the world’s largest retailers, food packaging companies, have all signed up to become members of the movement and signed up to the Plastic Pact in their localities to bring about meaningful change.

Share it

Useful Links

THE HISTORY OF PLASTIC

Throughout the history of plastic, PET has been crucial in keeping food fresh with lightweight and durable packaging solutions that have helped reduce food waste for almost a century. Learn all about the invention of plastic and the important role it has played feeding people and saving the lives of humans and elephants in the adaPETation® timeline of the history of plastic.