If the PET polymer industry is to find its way towards a regenerative path it will be life-mimicking organizations that help take it there.

While there are undisputed benefits to the world’s most easily recycled plastic including its life- and energy-saving properties, the most degenerative aspects of the polymers like PET still need to be addressed.

Plastic’s contribution to the degradation of our environment through greenhouse gas emissions and the accumulation of plastic waste in our ecosystems results from our collective inability to fully recycle the precious material.

For all the marvelous benefits the material has had on our lives, our inability to close the loop on its production is only too visible in viral videos like the one published by the Oceans Cleanup showing a tsunami of trash in Guatemala.

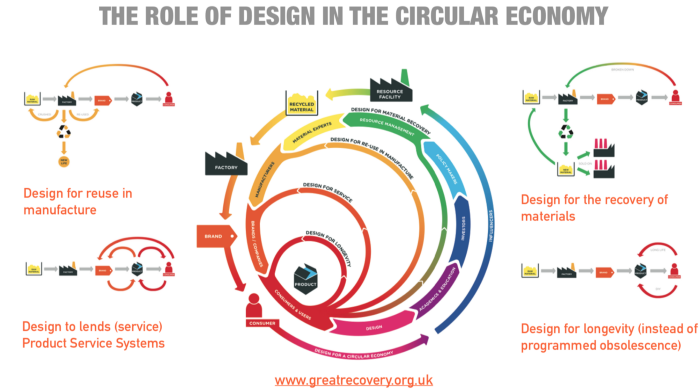

However, it will take more than a host of beach and river cleanup operations to bring the material into line with the needs of the planet. Turning off the plastic tap further upstream is a matter of extreme complexity that requires system thinkers to design for longevity instead of programmed obsolescence.

Those charged with implementing the UN global treaty to end plastic pollution signed in April 2022, will need to focus on organizations that are able to mimic nature and plug in to 3.8 billion years of research and development to address the complexity of our species’ interdependence with the material if they have any chance of success.

Regeneration Rules

Fortunately it doesn’t require one person, or one organization, to come up with the solution. Networks are already being developed to nurture the life-mimicking organizations of the future. It is these organizations that will inevitably find solutions to the biggest problems we face as a species, according to systems thinker, Jay Bragdon.

Changing the paradigm from degenerative to regenerative industries is something Bragdon writes about in his influential book, Companies that Mimic Life.

Bragdon highlights the superior performance of companies that put people and place on the balance sheet, an approach that he describes as Living Asset Stewardship.

Rather than following the industrial pack and prioritizing the preservation of capital assets, companies that engage in Living Asset Stewardship, place a higher value on living assets (their people and the environment in which they function) because they understand that living assets are, in fact, the source of all capital assets and, as a result, more important in the overall hierarchy.

These companies by placing their focus on living assets are very much designed for longevity, underlined by the findings of Bragdon’s study of the long-term performance of these companies.

“Companies that mimic life see the world as it actually is: a self-regulating, complex, adaptive system whose defining property is life – not a mechanical system that works by a fixed set of laws,” he says.

Bragdon outlines how life-mimicking organizations on the stock exchange were able to outperform companies from the “business as usual” school of thought.

The Global Living Asset Management Performance (LAMP) Index – a learning laboratory of sixty corporate pioneers in living asset stewardship – highlights how companies that were pioneers in a management genre that mimicked the organization and behavior of living systems, outperformed the FTSE-100 and S&P 100 by a factor of 74% and 56% respectively between 1994 and 2019.

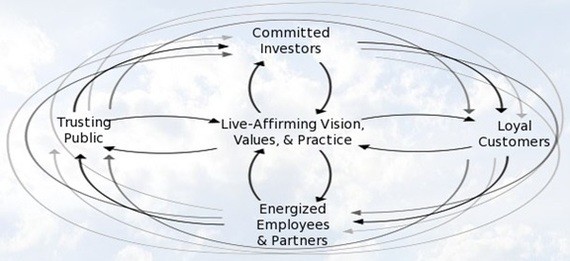

The virtuous circle of organizations that place life-affirming values and practices at the heart of what they can do can be seen in the diagram below.

Letting Life Take the Lead

“Instead of modeling themselves on the assumed efficiency of machines – a thought process that emerged during the industrial age – these firms model themselves on living systems” says Bragdon.

“Understanding that everything of value ultimately arises from life, they place a higher value on living assets (people and Nature) than they do on nonliving capital assets. The energy they invest in stewarding those assets – a practice we call “living asset stewardship” is transformative.”

These are the original disruptors, companies capable of transcending the orthodoxy of current economic thinking of unlimited economic growth without considering the boundaries of the planet.

“Instead of exploiting people and Nature, which creates systemic resistance, they nurture both, which creates flow and harmony. When you step back and think of this approach, it makes sense,” says Bragdon. “Companies are inherently living systems, communities of people with shared goals, living and working at the intersection of biosphere and society. And here is the rub: within this web of life there resides enormous intelligence, much of which remains untapped.”

“Life-mimicking companies tap into this intelligence in two key ways: Through mimicking natural processes in the ways they produce goods and services (via industrial ecology) By awakening the spiritual intelligence of employees, which resides in the interconnected neurology of their hearts, brains, and guts.”

According to Bragdon, life-mimicking companies all place the following values at the heart of their organization.:

- Decentralized, self-organizing networked structures, whose component parts serve the health of the whole (such as the human nerve system and the cognitive architecture of our brains).

- Regenerative life strategies that increase opportunities for survival, reproduction, and improving cultural DNA.

- Frugal instincts that seek to optimize use of resources.

- Openness to feedback that enables adaptive learning.

- Symbiotic behaviors that link individual wellbeing to the health of the larger systems in which they exist (biosphere, society).

- Consciousness of capabilities, interdependences, and limits.

The sixth, says Bragdon, “is an emergent quality that grows as the other five attributes become more developed, and is important because it guides the capacities of companies to make intelligent decisions.”

The ability to make intelligent decisions at a time of unprecedented complexity will be key to leading others towards a regenerative path.

Giles Hutchins, the cofounder of Biomimicry for Creative Innovation and author of Future Fit, writing in the foreword to Bragdon’s book argues:

“Increasingly, as our organizational context requires us to become ever more emergent, innovative, and adaptive, so leadership must become more about empowering, empathizing, encouraging interconnections, innovation, learning, local attunement, reciprocating partnerships, and an active network of feedback,” he says.

“As such, the aim of leaders becomes more focused on nurturing conditions where the organizational living system can unlock its creative potential, learn, and flourish in a purposeful and coherent way, so that it can create and deliver value while being mindful of the wellbeing of all the people it serves and the wider fabric of life it relates with.”

Real Life Examples

The best examples of life-mimicking organizations highlighted in Bragdon’s study come from a broad spectrum of industries, including consumer goods conglomerate, Unilever, pharmaceutical company, Novo Nordisk, sports goods giant, Nike, steel manufacturer Nucor, packaging and adhesives corporation, Henkel, and the Australian financial group, Westpac Banking.

Rated as one of the world’s most ethical and sustainable companies, Unilever saw its share price appreciate more than 200% between 2000 and 2015, roughly five times more than global benchmark indices and 1.3 times more than its primary competitor, Procter & Gamble at a time when it was underlining its credentials as a life-mimicking organization with the implementation of its Sustainable Living Plan. It was not a coincidence that this happened at the same time as it was implementing its ambitious plan to radically lower its global ecological footprint while raising living standards in developing countries, where it sources many of its raw materials and doubling down with the acquisition of companies with a similar outlook.

In the pharmaceutical sector, Novo Nordisk has become the profit leader of the global pharmaceutical industry by inspiring employees to think in a resource-conserving, holistic context. Because of its commitment to responsible frugality, Novo has remained virtually debt-free, writes Bragdon, giving it the liberty to deepen its explorations into industrial ecology and to broaden its learning culture. Between 2000 and 2015 Novo’s share price appreciated more than 20-fold, while those of Merck, Pfizer, and Lilly (Novo’s main competitor) all lost value. One of its plants in Denmark famously sits at the center of the Kalundborg Eco-Industrial Parks, a model of symbiotic industrial development.

Nike, on the other hand, Bragdon writes, uses innovation to pursue its symbiotic goal of effecting “environmental, labor and social change”, by freely sharing its knowledge on open-source platforms,

It has accelerated constructive change in the apparel industry. Since 2007, Fast Company magazine has six times rated Nike among the world’s top 50 innovative companies (#1 in 2013, #17 in 2014). Between 2000 and 2015, its shares appreciated more than 1,200%, about 25 times more than global benchmark indices.

Steel company Nucor, Bragdon argues, was able to reinvent the global steel industry by giving frontline employees the creative freedom to self-organize and network. At the heart of its organization is the harvesting of the knowledge of men and women doing the work. It quickly became the innovation, profit, and green leader of its industry with no research and development (R&D) department.

Westpac Banking raised its corporate consciousness by creating a culture “in which everyone is able to think clearly and creatively, to act ethically, and to air any issues or concerns absolutely without fear”, according to Bragdon. Long regarded as the world’s “most sustainable bank,” under CEO Gail Kelly it was named in 2014 the world’s most sustainable company. Between 2000 and 2015, Westpac’s shares appreciated more than 270% roughly four times more than those of JPMorgan Chase and its Moody’s credit rating (Aa2) was higher as well.

Regenerative Polymers

As the polymers industry seeks to close the loop by implementing the cradle-to-cradle thinking espoused by authors Michael Braungart and William McDonough, its being driven forward by companies and organizations that are life-mimicking and more often than not, the best students of nature.

By identifying carbon dioxide outputs from other industrial systems as an input for their own production of materials used to create bioPET, life-mimicking organizations like LanzaTech and Avantium are adopting symbiotic behaviors with a focus on the health of the larger systems in which they exist.

Frugal instincts that seek to optimize the use of resources are coming to the fore (with a little help from governments introducing regulations that require more recycling) prompting important investments in recycling networks and infrastructure being built up in response to mounting waste. Companies like Carbios and Agilyx are investing in a chemical recycling approach which could complement existing traditional mechanical recycling of PET to reduce the industry’s reliance on virgin fossil fuel sources significantly in the next 10 years.

Other companies conscious of complex interdependencies and the limits of the planet are focused on shifting away from the use of virgin fossil fuels towards the creation of biopolymers with biodegradable or renewable materials or alternatives to plastic.

Gingko Bioworks, ZeroCircle and Mori are just three examples of modern companies borrowing from biology and introducing nature-based solutions as a way to address contemporary problems, including food waste.

Not to mention the host of decentralized, self-organizing networked structures popping up like Precious Plastic, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Plastic Pacts and impact investment funds like Closed Loop Partners and Circulate Capital fuelled by funds from the biggest consumer goods companies and the polymers industry itself.

As Bragdon says: “Companies at the forefront of this revolution, by connecting to the immense resources of the human spirit, will survive and thrive through the challenges we now face. Those in denial will certainly fail.”

If you know of similar initiatives, the AdaPETation Network is keen to bring solutions together to encourage greater collaboration and more.

If you’re working on something that puts PET at the service of life we’d love to hear from you. Please join the network and share with us your initiatives.

Share it

Useful Links

THE HISTORY OF PLASTIC

Throughout the history of plastic, PET has been crucial in keeping food fresh with lightweight and durable packaging solutions that have helped reduce food waste for almost a century. Learn all about the invention of plastic and the important role it has played feeding people and saving the lives of humans and elephants in the adaPETation® timeline of the history of plastic.