Why it’s time to take the blame out of the plastics game and move towards whole systems thinking

A blame game between environmental activists, plastics producers and consumers has dominated the conversation surrounding the material and the environmental costs of its misuse.

This difficult discussion has for almost four decades frustrated the search for an effective solution to one of the most serious challenges facing our planet.

Feeding an insatiable appetite for an adversarial news cycle, there has historically been on one side environmental activists and NGOs demonizing plastic and on the other defensive producers and consumer goods brands seeking to push responsibility for plastic waste onto their customers.

The former makes little mention of the positive benefits of plastic and packaging and the role it has played in helping to solve some of the broader, more complex challenges that we face as a society, like that of food waste and how best to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by introducing lighter and cleaner materials for the transportation of food.

The latter hasn’t helped producers take a more constructive role in the conversation occurring around plastic waste, or stave off threats of new regulations, in particular, producer responsibility laws, which have already been introduced in Europe and are currently being debated in the US.

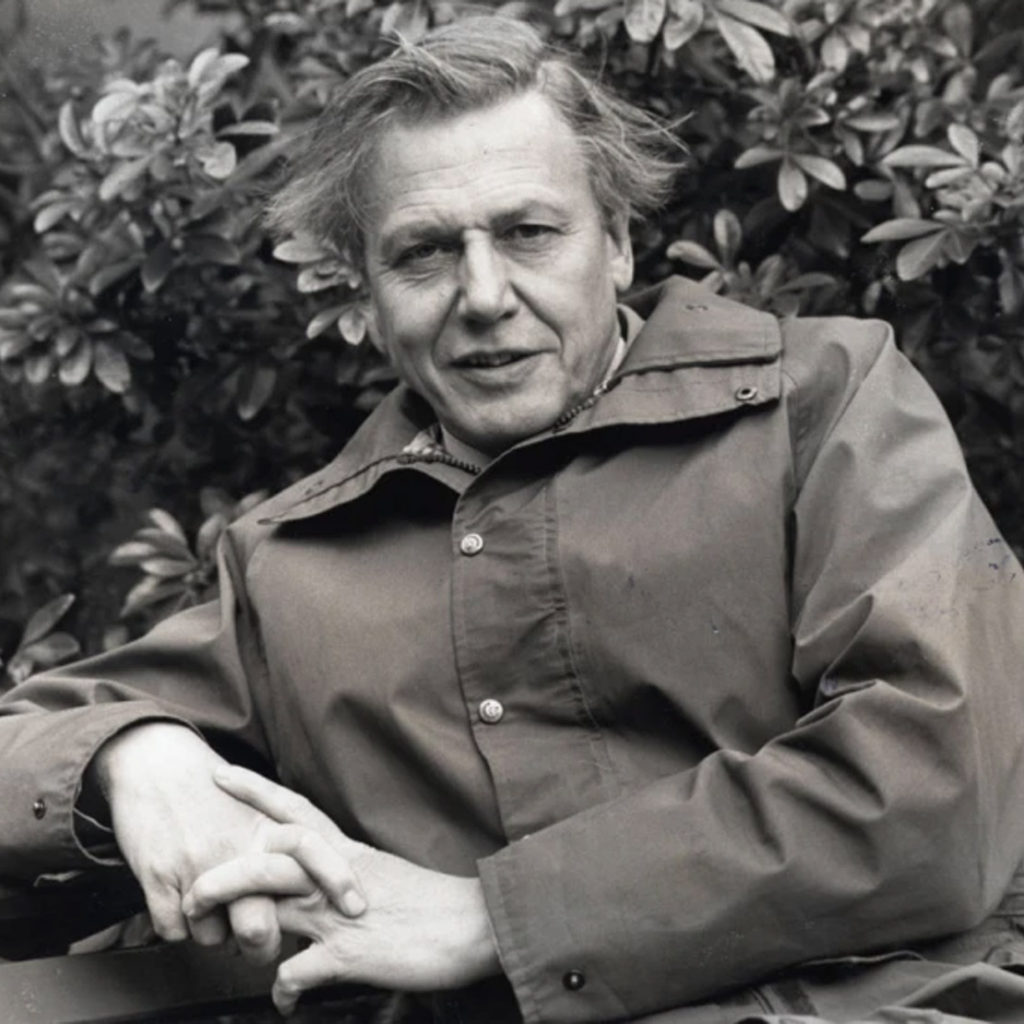

While accurate, the “we wouldn’t produce it if people didn’t want it” defence has started to wear thin, especially after the entry of influential figures, Sir David Attenborough and Dame Ellen MacArthur into the conversation.

The two staunch defenders of the oceans, along with other influential NGOs like Plastic Oceans have successfully highlighted the alarming leakage of plastic waste into our seas and turned the tide against the plastic industry.

Plastics Pugilist Division

The subsequent shift in public opinion has transformed the dynamics of the debate completely, and yet still the divisive dialogue remains entrenched.

It can be seen playing itself out in the US congress where the two schools of thought are visible in two rival bills working their way through the halls of power.

In the blue corner, the Break Free From Plastics movement, represented by senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and representative Alan Lowenthal (D-CA) who reintroduced the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act to “utilize proven solutions to protect impacted communities, reform our broken recycling system, and shift the financial burden of waste management off of municipalities and taxpayers to where it belongs: the producers of plastic waste”.

In the red (with a little bit of blue) corner, U.S. senators Rob Portman (R-OH) and Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) have introduced the RECYCLE Act, which is focused on helping “educate households and consumers about their residential and community recycling programs”.

The industry and the lobbyists have swung into action throwing their weight behind the latter bill, while activists push for the former.

A Deeper Understanding

A deeper understanding of the environmental consequences of these sorts of legislative moves has been an important part of the shift to a more collaborative conversation between both sides.

An investigation by Trucost, in 2014, was fundamental to broadening the conversation about the costs of replacing plastic with other materials, and looking in greater depth at the environmental impact of doing so.

Carried out in association with the American Chemistry Council representing the biggest polymer producers, the research employed Trucost’s ‘natural capital’ valuation techniques that identify nature as an asset, or set of assets that benefit people.

Trucost’s research suggested that the environmental cost of plastic in consumer goods was actually 3.8 times less than viable alternatives to plastic like glass, tin, aluminum and paper and that substituting plastic in consumer products and packaging with alternatives would increase environmental costs from $139 billion to a total of $533 billion.

This research and life cycle assessments for specific products like PET plastic and packaging offer a more complete picture of the complexities of removing these plastics from our supply chains and replacing them with alternatives.

“We can’t forget that plastics do provide significant benefits to society, including the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared to alternatives, decreased fuel usage, and increased efficiency in transport due to the lightweight nature of the material. However, when used plastics are not properly managed, they end up in the environment, jeopardizing the benefits. Therefore, it’s critical to manage trade-offs within a specific policy context,” says Steward Harris, Senior Director, Marine and Environmental Stewardship, Plastics Division at American Chemistry Council.

Add to this the difficulties in demonizing all plastics as the same, when some plastics like PET are cleaner and can be more easily recycled and it becomes even harder to make sense of the avalanche of ideas being introduced to solve the challenge we face to move towards a world free of waste.

Whole Systems Thinking

One of the biggest success stories of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) and the Plastics Pacts proliferating across the world has been the ability to rise above this divisive dialogue, by reaching an understanding that we will only be able to find a solution by working together.

“One thing I think is really interesting and powerful with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation is they pulled together all the key actors across the plastics value chain and brought everyone together so they can look at the problem from a systemic perspective and create solutions as a whole, as an industry, as a kind of value chain, and a wide ecosystem,” says Brian Bauer, in charge of Circular Economy & Alliances at Algramo, a winner of EMF Circular Design Challenge in 2017. The reuse solutions specialist backed by Closed Loop Partners, is working with global brands like Unilever to help them fulfill their pledge to design single-use plastics out of its product portfolio by 2025.

The adoption of whole systems thinking to understand how things are related, and how they influence one another within a whole has been an essential component in the shift towards an approach that mimics nature.

Focusing on cyclical rather than linear cause and effect, systems thinking can be applied to understand linkages among elements, cause and effect, feedback loops or to identify leverage points, which are places in a system that can be influenced or changed.

Making sense of everyone’s role and the decisions that need to be taken throughout the system is one of the biggest challenges.

Businesses have become increasingly aware that they are part of an interconnected, holistic system focused on the three dimensions of people, planet and profit. Previously represented as intersecting circles, whole systems thinking nests them together, placing business at the heart of society, which in turn is part of the wider environment.

To thrive, business must deliver value for all three, which the Future-Fit Foundation calls “system value”.

When we understand the components of a system and relationships between them we can begin to understand what affects them, and how to shift them into better patterns by working together.

According to Jacob Duer, president and CEO of the Alliance to End Plastic Waste there is no single solution to achieving a true circular economy for plastics, so improving conversations between public-private partnerships in organizations like the Alliance to End Plastic Waste are crucial. “These partnerships demonstrate the collective responsibility we share in combating the challenge,” he says. “Private sector, local governments and NGOs all bring various and critical expertise and experiences that are invaluable in developing meaningful solutions on the ground.”

Share it

Useful Links

THE HISTORY OF PLASTIC

Throughout the history of plastic, PET has been crucial in keeping food fresh with lightweight and durable packaging solutions that have helped reduce food waste for almost a century. Learn all about the invention of plastic and the important role it has played feeding people and saving the lives of humans and elephants in the adaPETation® timeline of the history of plastic.